This week, our In Focus, written by HMA Principal Jen Burnett in collaboration with the National Association of States United for Aging and Disabilities (NASUAD), summarizes key considerations and policy decisions contained in Electronic Visit Verification: Implications for States, Providers, and Medicaid Participants for state consideration as they work to implement electronic visit verification (EVV) systems in accordance with the mandate included in the December 2016 21st Century Cures Act (the CURES Act).

On January 1, 2019, new federal requirements for EVV go into effect, requiring the use of EVV for Medicaid funded personal care services. EVV technology has been available for more than two decades, but prior to the passage of the CURES Act, EVV was optional for states, providers, and managed care organizations (MCOs). It requires state Medicaid programs to implement EVV for Medicaid-funded personal care services by January 2019, and for Medicaid-funded home health care services by January 2023. This summary highlights the current state of EVV; the new requirements set forth in the CURES Act; the role of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS); and the approaches states may consider.

EVV: What It Is and How It Is Currently Being Used

EVV technology verifies that home and community-based services are delivered to individuals needing those services. Originally patented in 1996, EVV technology continues to evolve and improve, with multiple vendors available to states, managed care organizations (MCOs), and providers. There are several technologies used for EVV, including:

- Telephone timekeeping with telephony: Requires the use of the individual’s telephone at the time of the visit. It can utilize a landline available in their home, or a smartphone/cell phone used by the personal care provider or the individual when a landline is not available.

- Web or phone-based applications using Global Positioning Service (GPS) verification: Relies on a mobile application, which is a GPS-enabled “clock” that indicates when service begins and ends. The worker “clocks in” and “clocks out” using their smartphone or tablet.

- One-time password generator using a key Fixed Object (FOB): Uses a “fixed object,” known as a key FOB, which is placed in the home of the individual and is attached to something in the home, like a drawer pull. The FOB generates a one-time password or code when the service provider arrives and when they leave.

- Biometrics: Verifies that the appropriate personal care service worker or home health care worker is the person providing the service using biometric identifiers such as voice recognition, fingerprints, iris or facial scan.

The New Driver Behind EVV: The 21st Century CURES Act

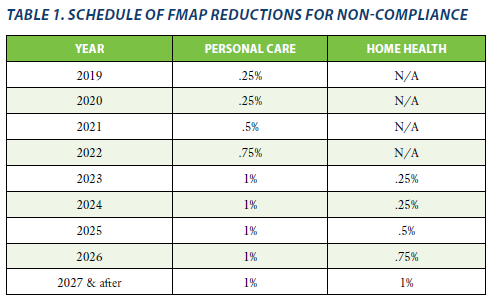

Enacted on December 13, 2016, the CURES Act is considered to be landmark legislation for health care quality improvement through innovation. Section 12006 of the CURES Act requires state Medicaid programs to implement EVV for personal care and home health care, or face reductions in their federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) beginning in 2019 for personal care services, and in 2023 for home health care services. Drivers behind the EVV mandate in the Cures Act include a projected 26 percent growth in personal care service providers from 2014–2024, due to demographic growth in the population needing these services, but more importantly, because people prefer to receive services in their own homes.

Implementing EVV: The Role of CMS

The CURES Act sets forth specific CMS responsibilities related to EVV. These include:

- Collecting and disseminating best practices to state Medicaid directors, with respect to training individuals who furnish personal care or home health services, as well as family caregivers and participants.

- Tracking state progress and implementation timeframes, and making adjustments to the FMAP paid to states that do not meet compliance deadlines, in accordance with the reductions outlined in Table 1 below:

- Providing assistance to states and other stakeholders, including surveys and webinars (for links to CMS presentations related to this assistance, see the full report).

- Establishing and managing an Advanced Planning Document process for review and approval/disapproval of state requests for enhanced match when the EVV system is operated by the state (or a contractor) as part of the Medicaid Enterprise System.

Implementing EVV: What States Need to Know

The CURES ACT sets forth state responsibilities and FMAP regarding the implementation of EVV. These include:

- The consequences for not complying with the law: FMAP reductions and timeframes are specified in Table 1 above.

- Specific elements that must be electronically verified, including:

- The type of service performed;

- The individual receiving the service;

- The date of the service;

- The location of service delivery;

- The individual providing the service; and

- The time the service begins and ends.

- Expectations for stakeholder engagement and training: The CURES Act requires states to take into account the considerations of a variety of stakeholders as they plan, design and implement EVV, including providers, participants, family caregivers, people who provide direct care, and other stakeholders.

Implementing EVV: State Program Design and Implementation

A 2017 National Association of Medicaid Directors/CMS survey of states found that there is wide variation in the status of implementation with less than a year to go before the implementation deadline. While not all states responded to the survey, CMS identified five design approaches to EVV implementation and shared them with states/stakeholders in December 2017. CMS identified five design models:

- Provider Choice: The state sets minimum standards for the EVV system and allows each provider to select their own vendor or system to use.

- Managed Care Organization Choice: In states that use MCOs to deliver some or all Medicaid funded personal care services or home health care services, the state could allow MCOs to select their own EVV vendor (akin to the provider choice model). MCO network providers would then use the EVV system mandated by the MCO with which they are contracted.

- State-Procured Vendor: The state competitively procures an EVV vendor that all providers in the state must use.

- State-Developed Solution: The state develops its own EVV system. Similar to the procured vendor model, the system is funded by the state and operates statewide.

- Open Vendor: This model provides both a statewide, state-managed (either procured or state-developed) system which is available to providers or MCOs who wish to use it, but also allows providers and MCOs to select their own EVV vendor.

Jen Burnett can be reached at [email protected].

Electronic Visit Verification: Implications for States, Providers, and Medicaid Participants Paper