In this week’s In Focus section, Health Management Associates (HMA) Managing Director MMS Matt Powers, Senior Consultant Kaitlyn Feiock, and Regional Vice President Kathleen Nolan look at the future of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). On November 10, 2020, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) heard oral arguments for California v. Texas, challenging the constitutionality and severability of the ACA. This challenge became possible after the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which zeroed out the individual mandate penalty for not purchasing health insurance. While most experts agree that an entire invalidation of the ACA is the least likely outcome based on the oral arguments, some uncertainty remains and more than $100 billion federal funds are at risk. The ACA standardized insurance rules offset premium costs for many individual market consumers and provided authority and funding for Medicaid Expansions in the overwhelming majority of states. The ACA also included other provisions that may be at risk but are not the subject of this note, such as the creation of Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) and the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office, as well as demonstration authority that has led to the creation of numerous coverage models. As states, Congress, and the federal executive branch face the possibility that the ACA may not survive in its present form, what mitigation strategies are available at the state and federal levels to stabilize uncertainties and protect against abrupt coverage changes?

Overview of Possible Outcomes of the Supreme Court Decision

We have summarized possible SCOTUS outcomes into three scenarios and set the table for discussion of possible state and federal government responses to scenario 3.Possible scenarios include:

- No change to the status of the ACA or the individual mandate.

- The individual mandate is determined unconstitutional but partially severable, invalidating some private market components of the ACA but leaving intact elements like the Medicaid expansion.

- The individual mandate is determined unconstitutional and inseverable, invalidating the ACA in its entirety.

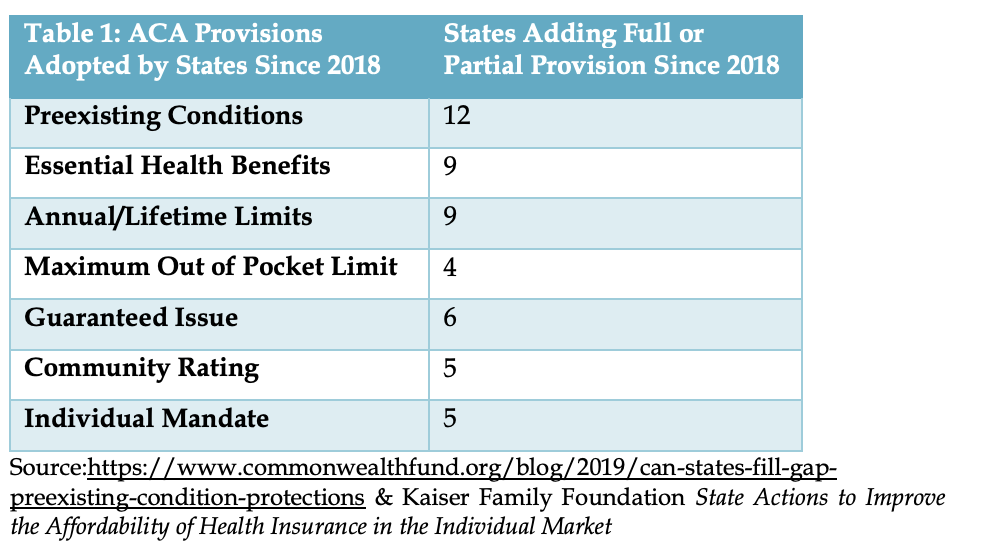

States can make changes to protect coverage provisions of the ACA States have always had a great deal of authority to shape their health insurance markets and Medicaid programs, and changes to state regulated insurance markets can be made without federal approval. Even prior to the ACA, some protections for pre-existing conditions were in place in the form of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act’s (HIPAA’s) requirement that states adopt guaranteed issue policies or pursue the option for high risk pools. However, eligibility for these protections was very narrow compared to the corresponding protections in the ACA, and high-risk pools presented underwriting and financial challenges that seemed to present difficulties potentially affecting affordability. Since 2018 when the current ACA lawsuit started, multiple states have codified ACA provisions in state law, as Table 1 demonstrates. Not captured in Table 1 below and this analysis are all of the existing market protections that states adopted over the years. Many of these were preempted by the ACA and allowed to lapse in state code but could be reinstituted to mitigate the impact of ACA repeal.

States should consider whether to act to reduce the risk of sudden federal policy change by establishing trigger laws and/or Section 1115 waivers that prevent disruptions to coverage, continue patient protections to the extent they apply, and ensure premium affordability in the event of ACA invalidation. Several states already have the opposite “trigger law” for their Medicaid Expansion, saying that if the 90 percent ACA Expansion matching rate is rescinded, the Expansion automatically shuts down. That aside, states have the following options to avoid potential major disruptions:

- Authority to cover the Medicaid Expansion population through an 1115 waiver remains an option, but without the ACA this coverage would be at standard matching rates rather than the 90 percent ACA Expansion matching rate (e.g., the current Wisconsin waiver).

- Even without state action, individual market policies will remain in place through 2021 for individuals enrolled in coverage when a SCOTUS decision is released in May or June of 2021.

States may continue the trend of tapping into certain ACA provisions to make changes like the state-based individual mandate in California and the insurance Marketplace changes underway in Georgia. Detailed state level work is needed to understand how many people and states are at risk should the ACA be fully invalidated, and that would include a review of current laws related to the indirect impact of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) on coverage rules.

If the ACA is Invalidated, Financing of Continuing Coverage Would Fall to States

Given states’ authority to enact state-based ACA-like insurance provisions or to enact Medicaid Expansion-like coverage through an 1115 waiver, the funding for marketplace subsidies and the federal matching differential emerge as the critical questions. Whether states can afford to pay more to cover existing Expansion enrollees was an issue prior to 2020. As most economic projections point to a prolonged recovery and COVID-19 pandemic-induced fiscal pressures and uncertainties are expected to continue in most states, it is unrealistic to expect that states will be able to handle an additional state funding burden in 2021.

Nationally, 86 percent of marketplace enrollees receive premium assistance and half get cost sharing reductions. While the percentages vary by state, in all states a majority of enrollees have help paying for their coverage. If SCOTUS strikes down the ACA entirely, the federal marketplace goes away and financial assistance to enrolled consumers will end. Without help paying for premiums, many enrollees will likely drop coverage within months, leaving states to determine whether to fund premiums for their residents. Currently, California is the only state that has a state premium support program for eligible marketplace enrollees.

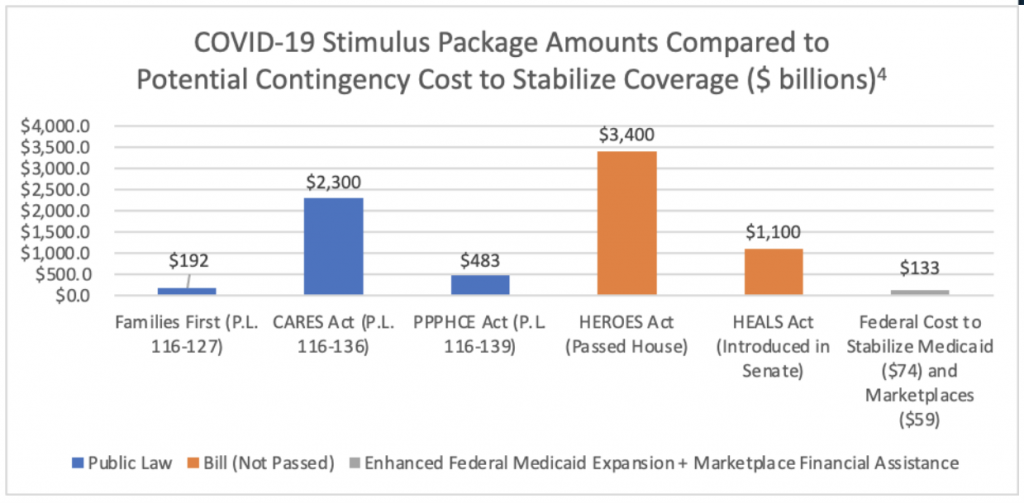

Authorizing a Contingency $133 Billion to Stabilize the Health Care Infrastructure During COVID

The two main federal funding sources that are already calculated in the federal budget and potentially concerning to states are the Marketplace subsides and the 90 percent ACA Expansion match. The ACA directs about $59 billion in federal subsidies to the marketplaces in 2020[1] and is estimated to have directed an additional $74 billion through the 90 percent ACA Expansion matching rate for those eligible through Medicaid expansion in 2018[2] for a total federal ACA cost of about $133 billion. If the ACA were to be invalidated, states may choose to cover Medicaid expansion-eligible individuals with standard match, for an additional state cost of approximately $30 billion.

Prior to enactment of the ACA, availability of state funding restricted most states from experimenting with expanded Medicaid coverage or implementing commercial market reforms. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, state budgets are in more precarious positions than they have been since the ACA passed. In the event of a full ACA invalidation that removes the Medicaid expansion funding and the Marketplace subsidies, federal and state coordination (and perhaps opportunities presented with COVID-19 relief bills) will be essential. In the context of not only the overall health care market ($4 trillion), but moreover the previously enacted multi-trillion dollar COVID-19 stimulus packages, [3] reaching consensus on $88-$133 billion to preserve coverage is within the realm of possibility.

A Short-Term Path to Stabilize the Health Care Infrastructure During the Pandemic and Avoid Uncertainty Related to ACA Invalidation

The fate of the ACA as we know it hinges on the SCOTUS decision expected in May or June 2021. A short-term path to stabilize the health care infrastructure may be more plausible now relative to just weeks ago:

- No major federal law changes would be required for a short-term stabilization. The components of the ACA are well within the boundaries of statutory authorities at the state and federal level. In many ways, the state laws codify policies operational today and are essentially trigger laws.

- Funding for a short-term stabilization prior to a SCOTUS decision would not have a substantial impact on the federal budget, as ACA spending is already calculated in the Federal budget. This is simply a matter of changing the method of distribution of the $133 billion (i.e. marketplace subsidies and Medicaid match) built into spending baselines. Without stabilization, states have authority to cover the Medicaid Expansion population through 1115 waivers but without the ACA, this coverage would be at standard matching rates.

- Last week’s signal from Senator McConnell calling for a 2020 COVID-19 relief package presents an opportunity. The fact that the next round of COVID-19 options are estimated to cost $1 trillion and $2 trillion suggest that there may be room for a component to stabilize ACA funding. Beyond stabilization, just as ACA closed the unpopular “donut hole” cost sharing provisions in Medicare drug coverage in Part D, providing some modest funding for state Marketplace flexibilities is one path to improve what ails Marketplace affordability. Just weeks ago, Senator McConnell expressed a willingness to fix the Affordable Care Act and not throw it away.

- Marketplace enrollees reflect a diverse political constituency that leaders at the state and Federal level will be hesitant to upset. It’s notable that the largest percentage of people in the $30,000-$100,000 income cohort identify as political Independents and the second most likely party identification in this income cohort identify as Republicans, albeit by a small margin. It is also worth noting that these are often the populations most affected by COVID’s economic impacts.

- States may continue to move to drive down Marketplace premiums and the number of people uninsured by codifying the individual mandate. California, the District of Columbia, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont all have a mandate in place. It’s estimated that all would experience significantly lower health insurance premiums and the number of uninsured would be decrease substantially as well.

Ultimately, the essential questions facing the healthcare system will not be answered for some time to come. There will be considerable unwinding to be done should there be even minor changes to the ACA. But even as we await a SCOTUS decision, states and Congress could act to provide a stable path for important protections and consumer supports within existing federal outlays. On a stand-alone basis such an effort may be politically difficult, but contingency funding through a stimulus mechanism is straight-forward and could be followed with regulations that accommodate states through distribution routes to give states the flexibilities to stabilize disruption and piece together similar protections. States will very much continue to have a large say with health insurance. They will also need to act to ensure that they have the necessary authorities and infrastructure. So, while it is possible to substantially limit disruption, it requires concerted action at the State and Federal levels, and stakeholders willing to engage on making it work.

For questions, please contact Matt Powers.

Read the full version of this article, including an ACA timeline and ACA by the numbers.

[1] https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-05/55085-HealthCoverageSubsidies_0.pdf

[2] https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-expansion-spending

[3] Families First. http://www.crfb.org/blogs/families-first-coronavirus-response-act-will-cost-192-billion; CARES Act. http://www.crfb.org/blogs/whats-2-trillion-coronavirus-relief-package; PPPHCE Act. https://www.crfb.org/blogs/whats-fourth-coronavirus-package. HEROES Act. http://www.crfb.org/blogs/whats-3-trillion-heroes-act; HEALS Act. http://www.crfb.org/blogs/whats-11-trillion-heals-act.