This week, our In Focus section is led by Matt Powers, a Principal in our Chicago office, who worked with HMA colleagues to summarize the factors that non-expansion states weigh when considering whether or not to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Including the states where Medicaid expansion ballot initiatives passed, 37 states have chosen Medicaid expansion or are moving toward Medicaid expansion. More than 12 million newly eligible individuals are insured by state Medicaid programs through the expansion. Comments on recent ACA Court Ruling:

Prior to our discussion of Medicaid expansion considerations, we first consider the implications of last week’s ruling on the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act. A federal district judge in Texas ruled Friday that the ACA is unconstitutional but gave no injunctive relief, therefore leaving the law legally and practically in place while the case moves to appeal. The root of the court’s decision is that, when the Supreme Court first upheld the ACA in 2012, the decision stated that the individual mandate would have been unconstitutional under the commerce clause. The Supreme Court upheld the individual mandate however, and the bulk of the ACA, because it was coupled with a tax penalty and therefore permissible under the taxing power given to Congress by the Constitution. Once the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act reduced the penalty to zero, twenty attorneys general sued to have the law invalidated on the basis that the individual mandate could no longer be considered part of a tax structure and therefore was unconstitutional under the commerce clause; an interpretation that U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor agreed with in his ruling Friday. More importantly, O’Connor ruled that the individual mandate was inseverable from the rest of the ACA provisions and therefore the entire ACA was unconstitutional. The case will soon go to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeal and possibly the Supreme Court. These appeals could take up to two years to reach the Supreme Court.

The court’s decision is almost entirely based on arguments made in the earlier case and findings of Congress that the individual mandate was essential and that all the provisions of the ACA were to “work together.” In the next rounds of appeals, even if the ruling on the individual mandate is upheld, there will be close scrutiny of the ruling that this provision was inseverable from the rest of the ACA.

While the case works its way through the courts, we don’t anticipate any impact on current Medicaid expansion states, or states with immediate plans to implement Medicaid expansion. However, it is possible that the verdict is considered during Medicaid expansion discussions in non-expansion states, along with a number of other factors that we discuss in more detail below.

Looking Back – Adoption of the Original Program and the Adoption of Medicaid Expansion

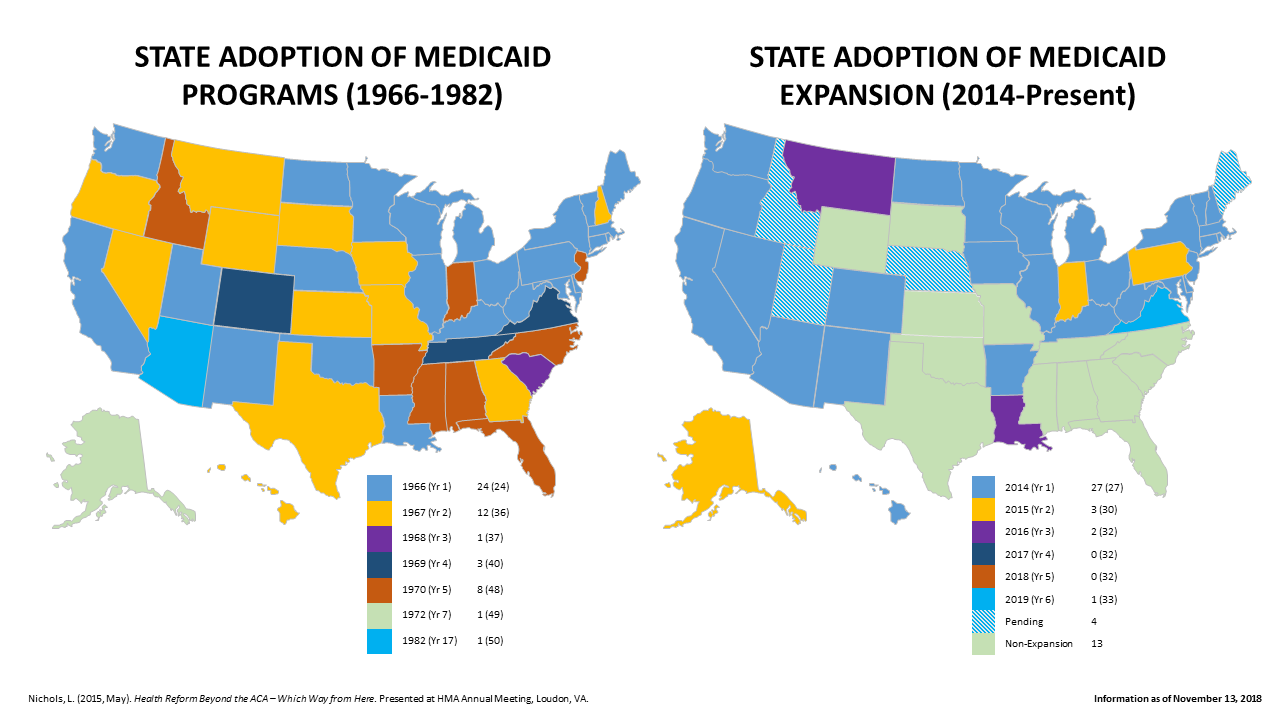

While the court ruling represents in many ways the back-and-forth intensity of the current political times, the dynamics at the time of the original adoption of the Medicaid program were every bit as compelling. As Figure 1 notes, it took 16 years for 50 states to adopt Medicaid programs. While 49 states adopted the program by 1970 (five years after the bill creating the Medicaid program was signed) the last holdout, Arizona, did not adopt Medicaid until 1982 – a full 12 years after the 49th adoption. There are certainly parallels between the order in which states adopted Medicaid and the order in which states adopted Medicaid expansion, as Figure 1 demonstrates.

Some key assumptions were made in the categorization of states in Figure 1:

- Wisconsin is considered an expansion state due to childless adults being covered under the BadgerCare program that pre-existed the ACA;

- Idaho, Utah, Maine and Nebraska are categorized as pending given the successful Medicaid expansion ballot initiatives in those states;

- Kansas remains in the non-expansion category due to the opposition of the state legislature, although the election of a new Governor who supports expansion may boost the chances of expansion in 2019 or in subsequent years.

Figure 1 – Adoption of Medicaid in 1966 Compared to 2014 Medicaid Expansion Provisions enabled by ACA

Source for 1966-1982 Map: Nichols, L. (2015, May). Health Reform Beyond the ACA – Which Way from Here. Presented at HMA Meeting, Loudon, VA.

What States are Next to Watch?

After the 2018 November election and ballot initiative results, 37 states have adopted or are poised to adopt Medicaid expansion. Voters in Utah, Nebraska, and Idaho elected to expand Medicaid on their 2018 midterm ballots. Each of these states has discussed work requirements for Medicaid enrollees, and Utah has drafted a waiver.

Figure 2 identifies the remaining non-expansion states and provides context as to the size of the potential expansion population relative to existing Medicaid enrollment. A subset of non-expansion states to watch are states that allow ballot initiatives – Florida, Oklahoma, Missouri, Mississippi, and Wyoming. Additionally, hospital and hospital associations continue the push for expansion, either at the statewide level or even a regional approach, as hospitals exhaust substantial (and frequently unmatched) resources as required by the EMTALA law to provide medical screenings and treatments for emergency medical conditions.

Figure 2 – 13 Non-Expansion States Medicaid and Coverage Gap Populations

| State | Current Medicaid Population[1] (September 2018) | Population Currently in Coverage Gap (<100% FPL)[2] (2016) | Percent of Current Medicaid Population | Percent of Total Population in Coverage Gap |

| Alabama | 910,008 | 75,000 | 8.2% | 3.5% |

| Florida | 4,224,719 | 384,000 | 9.1% | 18.0% |

| Georgia | 1,764,356 | 240,000 | 13.6% | 11.2% |

| Kansas | 384,737 | 48,000 | 12.5% | 2.2% |

| Mississippi | 634,950 | 99,000 | 15.6% | 4.6% |

| Missouri | 921,839 | 87,000 | 9.4% | 4.1% |

| North Carolina | 2,033,474 | 208,000 | 10.2% | 9.7% |

| Oklahoma | 783,354 | 84,000 | 10.7% | 3.9% |

| South Carolina | 1,012,160 | 92,000 | 9.1% | 4.3% |

| South Dakota | 116,882 | 15,000 | 12.8% | 0.7% |

| Tennessee | 1,377,849 | 163,000 | 11.8% | 7.6% |

| Texas | 4,329,625 | 638,000 | 14.7% | 29.8% |

| Wyoming | 57,554 | 6,000 | 10.4% | 0.3% |

| TOTAL | 18,551,507 | 2,138,000 | 11.5% |

Much of the discussion and concerns identified by non-expansion states focus on states’ share of the cost, which will be 10 percent in 2020 and beyond. This is a sizeable outlay for the states and many state legislators fear that the federal government may turn out to be a less reliable partner due to the rising federal debt and the potential for future Congressional efforts to curb entitlement spending. Some states consider non-disabled adults without dependent children as a sector of the population that warrants a different set of considerations and rules. Beyond the federal matching and partnership issues, difficulties expressed in the debate include trying to keep up with state innovations and understanding what CMS has approved. Many of the 37 states that have expanded Medicaid have their own twist on the expansion, with significant policy variations. Even with the recent court ruling, it is very likely that Medicaid expansion will remain part of the fabric of state policy and that states will continue to debate about expansion. What follows is an attempt to provide insights into the dynamics for non-expansion states with lessons learned incorporated from the 37 states that have adopted expansions.

Key Issues that Factor into State Decisions Regarding Medicaid Expansion

- Waiver Flexibilities Granted Under Current Administration May Not Be Available After 2020. Of the remaining 13 non-expansion states, 11 will have Republican Governors in 2019 and all 13 states will have Republican majorities in both legislative chambers. The Trump administration has been willing to approve, via 1115 waivers, limitations not allowed in the Medicaid programs under the previous administration. Knowing the current administration is in place may bode well for consideration of expansions in the remaining 13 states as the political alignment may help diminish the political discourse at the state level. Additionally, states may find it advantageous from both financial and policy perspectives to learn from the “early adopters’” mistakes and choose from a menu of CMS-approved adoptions, such as expanded cost sharing and differential benefit designs (as was approved in Indiana), or work requirements. Partial waiver proposals that would expand Medicaid in a limited geographical region, but not statewide, are worth watching as well. Most of the recent expansions include some type of work requirements, also referred to as community engagement, for the expansion population. These work requirements vary on the spectrum of restriction, but have included provisions such as:

- Requirements to work a set number of hours per week/month, or be engaged in other activities (i.e., education or volunteering)

- Lockout and/or disenrollment from Medicaid if requirements aren’t met

- Reporting of exemptions and/or hours worked in a state monitoring system

- Exemptions for community engagement – generally medical frailty, pregnant women, disabled individuals, full-time students, family caregivers

It is also noteworthy that since the beginning of the 2016 election cycle (and before), while “repeal and replace” bills have been a point of contention in Congress, most of the introduced “repeal and replace” bills kept the Medicaid expansion in place. Rescinding coverage for 12 million newly covered Medicaid beneficiaries is politically unpalatable and the threat to Medicaid funding factored in the failure of “repeal and replace” bills in the past. These factors, along with the fact that the House will have a Democratic majority beginning in 2019, make consideration of an expansion repeal unrealistic in both the short and long term; supporting the point that there’s a unique window of opportunity before 2020.

- Financial Implications of Historic Proportions – non-Expansion States Dislike Sending Billions to Expansion States. Every year, state residents pay over $3 trillion in federal income taxes. The federal government keeps money for federally-led activities and effectively sends back funding to states and state governments through Medicaid, infrastructure, public health grants and other legislated program vehicles. This process of taxpayers sending money to the federal government and states receiving federal funds back to finance state/federal programs is a process that can be called “financial migration.” In 2018, it is projected that 55 percent of all federal assistance to state and local governments is derived from the Medicaid program federal match.[3][4] Interestingly, the 13 non-expansion states matching rate is 63.9 percent while the match rates of the 37 expansion states is just 58.6 percent. As such, states that have historically been the beneficiary of the higher matching rates are potentially now bringing down their effective matching percentage by not expanding.

While there are certainly more factors than the expansion in play, for approximation purposes only, Figure 3 compares pre-expansion to post-expansion (2013 and 2017 NASBO State Expenditure Reports[5]) and indicates that expansion states’ federal funds have increased by $97 billion (28 percent) while non-expansion have increased in that period by $4 billion (3 percent).

Figure 3 – Non-Expansion State vs. Expansion State Federal Fund Growth

| Federal Fund Growth ($) 2013 to 2017 | Federal Fund Growth (%) 2013 to 2017 | Federal Fund Growth Per Capita | |

| Non-Expansion (13 states) | $4,477,000,000 | 3.05% | $43 |

| Expansion (37 states) | $97,164,000,000 | 27.61% | $440 |

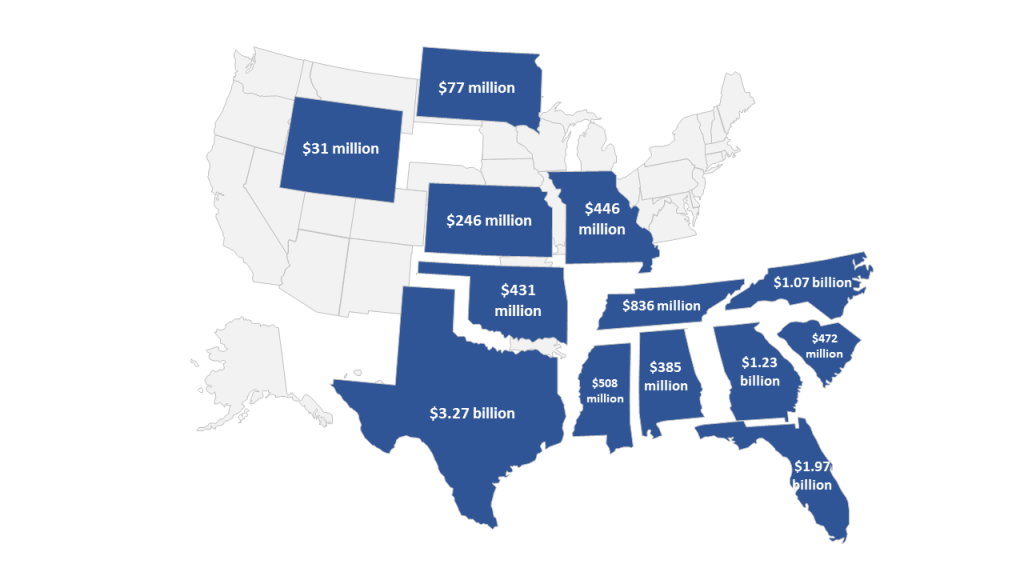

For an additional perspective, assuming the 2.1 million individuals in non-expansion states were to be covered at an approximately $475 per member per month (HMAIS calculations from public documents) capitated rate at the 90 percent federal matching rate, nearly $11 billion net federal dollars would flow to these 13 states annually at full participation/take up. While the $475 rate may be slightly high for the remaining 13 states as those states tend to be slightly lower cost states, the expansion choice clearly has material financial implications for states. Figure 4 illustrates how the nearly $11 billion annual monies would be available to support state enrollees and providers at full-take up rate, 90 percent federal match and a $475 PMPM

- Evidence suggests that States Realize General Revenue Fund Savings with Expansion. Setting aside the new resources that providers and patients see from expansion, many states have seen an immediate budgetary benefit. Although Medicaid expansion still will have a 10 percent state share in 2020, the short-term impact is often savings. This is because most non-expansion states are operating state-funded-only health programs, mainly in the areas of mental health and substance abuse as well as corrections. Individuals served in these programs overwhelmingly tend to be Medicaid eligible under expansion. As a result, there are opportunities to fund certain benefits with Medicaid funds that are matched at the higher expansion match rate. For states facing significant budget pressures, the Medicaid expansion funding source may be an attractive opportunity for short-term savings. In addition, when states use provider taxes to fund the state share of Medicaid expansion, these short-term general fund savings are even greater. Virginia, which is funding the state share of expansion with a hospital tax, has projected savings to their general fund of $421.6 million in the first two years of expansion.[6] Other states expecting general revenue savings from Medicaid expansion are Arkansas ($444 million total from 2018-2021)[7], Michigan ($1 billion from 2018-2021)[8] and Montana (over $50 million).[9]

Figure 4 – Potential Annual Funding Available to Remaining States

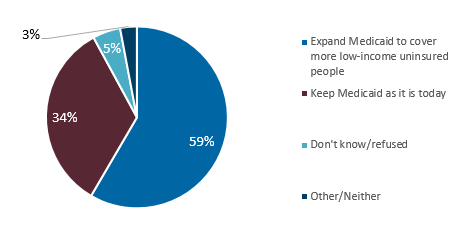

- Medicaid Expansion Polls Well in Non-Expansion States. As Figure 4 indicates, 59 percent of those polled in non-expansion states would support expanding Medicaid to cover more low-income uninsured people. Overall, the proportion in favor of the Medicaid expansion in Florida is similar to the share seen in other non-expansion states, with nearly six in ten residents saying their state should expand Medicaid, while nearly four in ten say their state should “keep Medicaid as it is today.” The majority of GOP voters in these states said they’d support a measure that “would expand Medicaid to people with incomes below $17,000 a year if they are single and $22,000 a year for a family of two,” including more than 60 percent of Republican voters in Idaho. Polling suggested that when ballot language was simplified, support for Medicaid expansion was even greater in these states than final vote tallies suggested. Although on many issues, polling results favorable to an initiative can be reduced when language is added about raising taxes to pay for the initiative, it should be noted that the ballot initiative to expand Medicaid in Utah passed despite the fact it included language authorizing a sales tax increase to pay for the expansion.

Figure 5 – Significant Support of Medicaid Expansion Among Those Living in Non-Expansion States

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Tracking Poll – November 2018: Priorities for New Congress and the Future of the ACA and Medicaid Expansion

- Business Wants a Healthy Workforce. Both private employers and state and local governments managing their work forces benefit if a viable and largely bipartisan path can be found to bring coverage to the uninsured. In many cases, workers are one illness or one accident away from being unable to work due to a lack of insurance coverage. One substantial hospital stay is frequently followed by the need for rehab and home care to recover and can lead to a “medical bankruptcy.” For those in the coverage gap who are not working, many have chronic conditions, including physical and behavioral health conditions; others are struggling to stay in school and incurring significant debt to do so; still others are caring for an aging parent or a child with disabilities, frequently leading to burnout that caused them to lose their job. There are reasons why many conservative-leaning business groups have frequently been supportive of expansion. Many employers realize that health coverage reduces absenteeism and turnover and improves productivity.

Figure 6 – Healthcare as Hub for State Pressure Points

- Expansion Offers Systematic Resources for State High-Pressure Points. Expansion gives states a more dependable, systematic resource that improves states’ abilities to manage what is currently a complex set of variables. The point applies to both every day catastrophes for real people with physical and behavioral needs as well as natural disasters. Examples include:

- Opioid Epidemic. As the leading cause of death for Americans under 50 years old[10], addressing the opioid epidemic has become an “all hands-on deck” movement. Medicaid expansion can play an important role in addressing the epidemic by providing access to treatment for affected individuals who otherwise would have been uninsured. In fact, expansion states have been able to use expansion funds for treatment (e.g. BH counseling; addiction treatment; Medication Assisted Treatment) so that they can use other federal resources for prevention while non-expansion states must use more federal resources for treatment since the expansion resources are not available.[11]

- Mental Health Gaps. Gaps in the mental health systems are frequently cited as an area that both parties agree need more resources and reforms. As policy-makers discuss the need for improvements, expansion potentially provides an organized hub for mental health treatment and services for at-risk populations.

- Incarceration Pressures. Medicaid expansion can provide ongoing healthcare support to individuals transitioning out of the criminal justice system. Both sides of the partisan aisle are looking for ways to work together for criminal justice reform and are searching for ingredients to reduce incarceration rates. Given the mental health and other system gaps, expansion presents a major resource to help with criminal justice reform.

- Natural Disasters. Expansion provides a consistent source of funding to hospitals and clinics that respond to community needs during natural disasters.

- Non-Expansion Cost Shifts to Employees and Employers. About one-third of all health care spending is Private Health Insurance (CMS NHE Tables).[12] Hospitals and clinics incur tens of billions of dollars in uncompensated care costs annually. HMA reviewed CMS S-10 reports for all 50 states and determined that Uncompensated Care reported to CMS by hospitals in expansion states decreased by 33 percent from 2013 through 2016 while increasing by 19 percent in non-expansion states. The increased uncompensated care is often passed on to privately insured patients, resulting in higher insurance premiums for employees and employers.

Figure 7 – Uncompensated Hospital Care by Non-Expansion State

| State | Uncompensated Hospital Care by Non-Expansion State (2016) |

| Alabama | $570,180,000 |

| Florida | $3,417,100,000 |

| Georgia | $1,833,240,000 |

| Kansas | $289,900,000 |

| Mississippi | $572,710,000 |

| Missouri | $1,037,230,000 |

| North Carolina | $1,652,740,000 |

| Oklahoma | $597,780,000 |

| South Carolina | $1,014,230,000 |

| South Dakota | $102,860,000 |

| Tennessee | $828,510,000 |

| Texas | $5,926,050,000 |

| Wyoming | $108,380,000 |

| TOTAL | $17,950,910,000 |

Source: HMA Analysis from CMS S-10 Reports, Dennis Roberts, Principal, Happy Retirement!

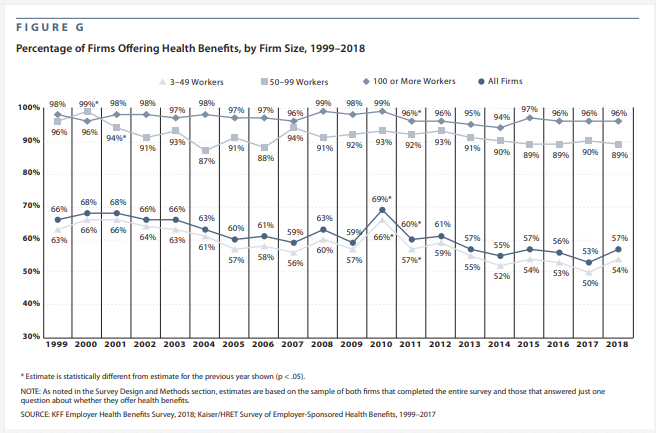

- The Concern that Medicaid Expansion Would “Crowd-Out” Employer Sponsored Insurance has not Materialized. Prior to the implementation of Medicaid expansion in 2014, there was concern that the expansion would create too large of an incentive for employers to dis-continue health care coverage for low-wage employees that would otherwise be eligible for Medicaid. As Figure 8 from the annual Kaiser Family Foundation Employer Benefits Survey points out below, this concern has not materialized. The percentage of all firms offering health benefits has remained unchanged in 2018 compared to 2013 at 57 percent.

Figure 8 – Percentage of Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

[1] https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html

[2] https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/

[3] Federal Medical Assistance Percentage for Medicaid and Multiplier. FY 2019. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federal-matching-rate-and-multiplier/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[4] Federal assistance to state and local governments by program is available in Table 12.3 at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/

[5] NASBO State Expenditure Reports 2013 and 2017. Retrieved from https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/state-expenditure-report/state-expenditure-archives

[6] DMAS Overview of Governor’s Introduced Budget http://sfc.virginia.gov/pdf/health/2018/010818_No1_Jones_DMAS%20Budget%20Briefing.pdf

[7] The Stephen Group, “Arkansas Health Reform Legislative Task Force: Final Report,” December 15, 2016, http://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/assembly/2017/Meeting%20Attachments/836/I14805/Final%20Approved%20Report%20from%20TSG%2012-15-16.pdf.

[8] John Ayanian et al., “Economic Effects of Medicaid Expansion in Michigan,” New England Journal of Medicine, February 2, 2017, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1613981.

[9] Bryce Ward and Brandon Bridge, “The Economic Impact of Medicaid Expansion in Montana,” University of Montana Bureau of Business and Economic Research, April 2018, https://mthcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/BBER-MT-Medicaid-Expansion-Report_4.11.18.pdf.

[10] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/06/05/upshot/opioid-epidemic-drug-overdose-deaths-are-rising-faster-than-ever.html

[11] ACA Repeal Would Jeopardize Treatment for Millions with SUD, Including Opioid Addiction. https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/aca-repeal-would-jeopardize-treatment-for-millions-with-substance-use-disorders

[12] National Health Expenditure measures annual U.S. expenditures for health care goods and services, public health activities, government administration, the net costs of health insurance, and investment related to health care. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet.html