Telehealth service expansions by Medicare and most Medicaid programs aim to rapidly increase access to care and reduce transmission, but also provide a natural experiment for policymakers.

This week, our In Focus section examines the extensive scope of flexibilities Federal and State governments have made to Medicare and Medicaid telehealth coverage in response to the COVID-19 national emergency. In March and April 2020, federal and state policymakers responded to the COVID-19 emergency by temporarily and aggressively expanding the definition of and reimbursement for telehealth services—moves intended to improve access to care and reduce virus transmission. Under the Medicare and Medicaid programs, these temporary expansions have been rapid and historic in scope, and will have substantial implications for patients, providers, payers, and federal/state financing. For policymakers, this temporary expansion may serve as a natural experiment for assessing which forms of telehealth services successfully expand access to care and should become permanent healthcare policy.

Leveraging the existing telehealth models along, the easing of restrictions: Telehealth services are currently fulfilling their long-touted benefits as a clinical solution to expanding access to care. For the benefit of both COVID-positive and COVID-negative patients these services have the ability to: extend a wide variety of care types to patients anywhere and at any time, reduce virus transmission rates by enabling social distancing, and enable providers to effectively triage patients amidst periods of high demand. While the basic structure of telehealth care is a patient/provider interaction via two-way video conferencing, there are several types of telehealth services clinicians can use to serve patients in the most appropriate manner. These include audio-only interactions (i.e., telephone calls) as a virtual check in, e-visits through an online portal, e-consults between providers, remote patient monitoring, and others. Importantly, payers define telehealth services differently from one another and establish reimbursement rules that differ by service type, provider type, and other characteristics. While consistency across payers can and should be improved, offering providers a menu of technology-based interactions that are free from overarching restrictions on location of services and other limitations, allows for the most flexibility in meeting the patients’ needs at the lowest cost.

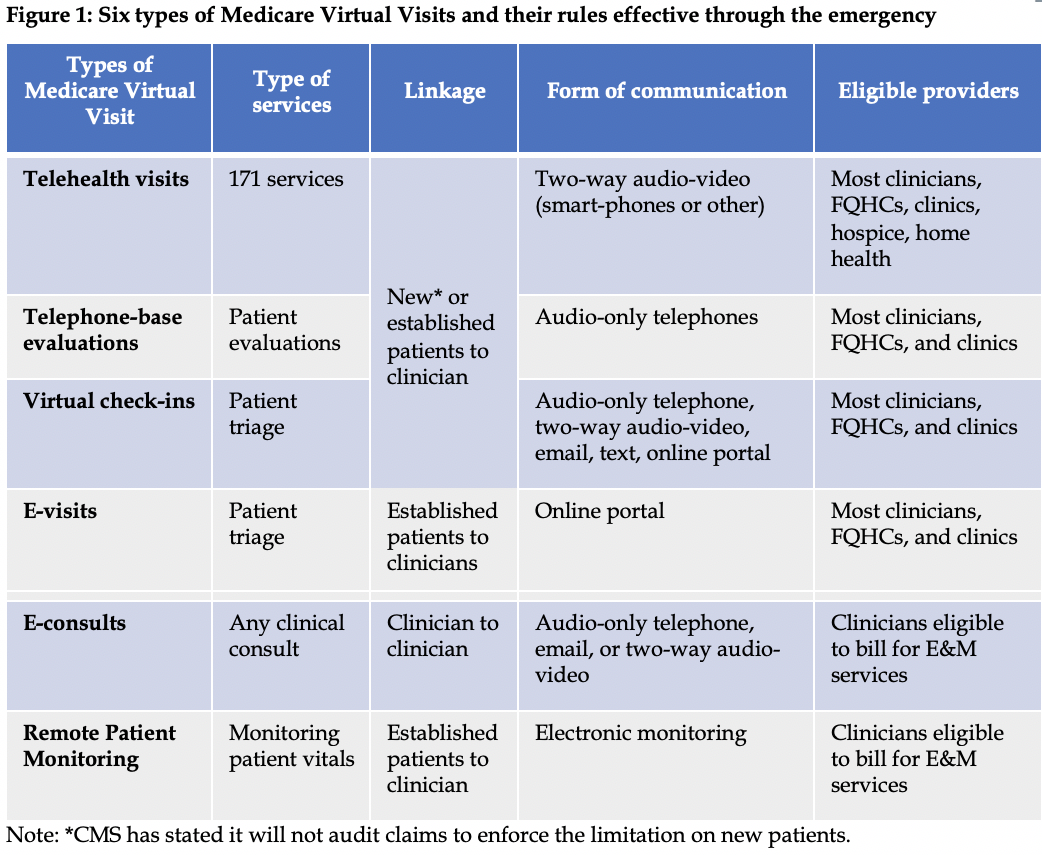

Medicare coverage expanded temporarily: Congress and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have temporarily expanded Medicare’s coverage of telehealth services through three regulatory or legislative vehicles, including the Cares Act of 2020. The scope of these expansions is extensive, impacting all six forms of Medicare telehealth services (Figure 1). Among the most important of these are the changes made to ‘Medicare telehealth visits’—physician office visits conducted via two-way audio/video. For this service Medicare will permit: visits to originate in urban areas and from the patients’ home, Federally Qualified Health Centers and rural clinics to act as distant sites, and 80 new types of services (e.g., emergency department, hospice, home health, and therapy services). While audio-only telephone calls are not permitted for this form of telehealth, audio-only telehealth is permitted by Medicare for ‘Telephone-based evaluations’ and ‘Virtual Check-ins’. The broad range of temporary expansions are retrospectively effective on March 1, 2020 and will remain in place until the end of the emergency. In addition, CMS is encouraging patients and providers to use the various forms of Virtual Visits implemented on a more permanent basis in the last 18 months (Virtual Check-ins and E-visits) and to be aware that, starting in 2020, Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are permitted to cover any form of Virtual Visit from anywhere. In addition, CMS will now permit telehealth encounters to be included in the risk adjustment process for setting MA plan rates.

Other federal policy expanded temporarily: Federal policymakers have also altered the telehealth landscape by creating flexibility under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and under the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). On March 17, the Secretary of Health and Human Services announced that the Office for Civil Right (OCR) will exercise enforcement discretion and waive penalties for HIPAA violations against health care providers that serve patients “in good faith” through everyday communications technologies, such as FaceTime or Skype, during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. In addition, during the emergency the DEA is permitting DEA-registered practitioners to issue prescriptions for controlled substances to patients on whom they have not conducted an in-person medical evaluation if the prescription is issued for a legitimate medical purpose, the practitioner is acting in accordance with federal and state law, and the practitioner is using an audio-visual, real-time, two-way interactive communication system.

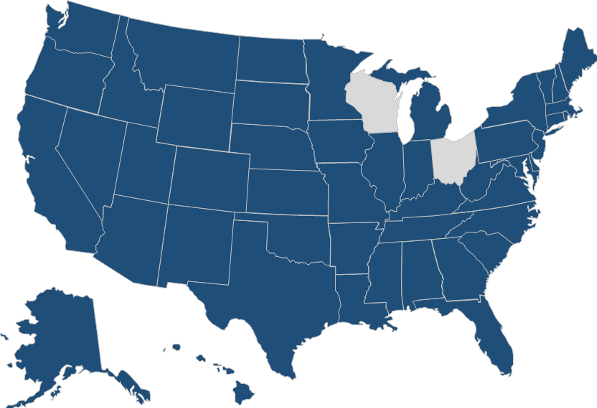

Medicaid policy expanded temporarily: To date, 48 states, Washington, DC, and several US territories have received approval for 1135 waivers from CMS to facilitate coverage expansion during the emergency (Figure 2). Several states are streamlining out-of-state provider Medicaid enrollment. In addition, many governors have used executive orders to further expand the definition of telehealth and are working to facilitate the use of telehealth in several ways. A number of states—including California, New York, and Delaware—have permitted the use of audio-only telephones for physician office visits and behavioral health visits. States such as Colorado, Washington and North Carolina have expanded the scope of eligible providers and types of clinicians permitted to bill for telehealth services. And other states—including Missouri, Texas and Indiana—now allow the establishment of a patient-provider relationship via telehealth or have eliminated patient cost-sharing for telehealth visits.

Figure 2: Forty-eight states receiving 1135 waivers from CMS to expand Medicaid coverage

Will telehealth use increase significantly during the emergency? While the recent expansions of telehealth coverage allow for a significant increase in the use of this service, the extent to which patients and providers will choose to use telehealth services is unclear. Prior to the emergency, the use of telehealth under Medicare was extremely low, amounting to roughly 0.3 percent of all Physician Fee Schedule spending per year—or $30 million. During the emergency, the use of telehealth services is likely to increase in urban areas and from patients’ residences. Physician offices, behavioral health clinics, FQHCs, home health agencies, and hospital systems specifically demonstrated a desire for these expansions, and subsequent relief upon their passage. In addition, increased use is likely to occur broadly across all payers, public and private.

Which of the temporary telehealth expansions will become permanent? This unfortunate emergency may serve as a natural experiment for policymakers assessing which forms of telehealth services could be expanded permanently. For many years, payers have voiced concern about the risk of fraud and misuse associated with telehealth services. By the fall of 2020, policymakers and payers will possess claims and encounter data identifying the volume of telehealth services provided in the first half of 2020, and an opportunity to survey providers and patients about their experiences with telehealth. Using these data, we will be able to determine which types of telehealth services were most beneficial to expanding access, in which locations service use grew most, and for which types of patients use grew most. Specifically, these data may answer questions such as:

- Are patients satisfied with and seeking these services?

- Do providers want to deliver these services?

- Should payers expand originating sites (e.g., urban areas and patient residences)?

- Should home health agencies, hospice agencies, and FQHCs serve as distant sites?

- Do audio-only telephone visits pose a significant risk of misuse?

Despite the natural experiment playing out right now, it may remain unclear—due to the corresponding decrease in in-person visits—if increased telehealth use leads to more cost-effective delivery or higher costs. In either case, these temporary, and potentially permanent, expansions of telehealth services will have budgetary implications for Medicare, Medicaid, and other payers.

Link to HMA’s Telehealth web page and slide decks

https://www.healthmanagement.com/what-we-do/covid-19-resources-support/telehealth/