In recognition of National Recovery Month this September, our In Focus section spotlights a new report from Health Management Associates, Inc. (HMA), Substance Use Disorder in California: A Focused Landscape Analysis. Published in August 2024 with support from the California Health Care Foundation, this analysis provides valuable insights into California’s substance use disorder (SUD) treatment system and offers actionable recommendations for improvement that can be applicable for other states.

The SUD Landscape in California

SUDs continue to be a significant issue both nationally and in California. In 2022, approximately 9 percent of Californians ages 12 and older met the criteria for SUD, compared with 16.5 percent nationally in 2021. The prevalence of SUD is also on the rise: in 2015, 8.1 percent of Californians ages 12 and older met SUD criteria, rising to 8.8 percent in 2022. Of the Californians struggling with SUD, only 10 percent received treatment for their condition, compared with 6 percent nationally in 2021. Overall, 81 percent of US adults who received care for SUD reported struggling to access necessary services.

California’s public behavioral health system siloes specialty mental health (MH) services, mild-to-moderate MH services, and SUD treatment services, resulting in a fragmented and inconsistent system that struggles to effectively support people with co-occurring conditions.

County plans administer specialty behavioral health (BH) services. They all have memorandums of understanding with the state’s Department of Health Care Services that are separate from the state arrangements to provide physical healthcare services. BH programs vary significantly across the state because counties operate them differently, with key variations in access policies, quality monitoring, services, and programming. Mild-to-moderate (non-specialty) MH benefits are administered by Medicaid managed care plans. Much of the state’s SUD treatment is operated by the Drug Medi-Cal Organized Delivery System (DMC-ODS).

Barriers to Care: Key Findings

System barriers prevent many Californians with SUD from accessing adequate care. Interviewees received a pre-interview questionnaire to determine the factors they believe have the greatest impact on access to SUD treatment. According to 11 out of 14 respondents, lack of access to housing and residential services is a “huge barrier” to SUD treatment.

Other barriers to care access, ranked in order, include limited access to food, transportation, and other social drivers of health (SDOH), SUD provider shortages, stigma against people with SUD, disparities in service availability across racial/ethnic groups and other populations, and complex referral and intake processes.

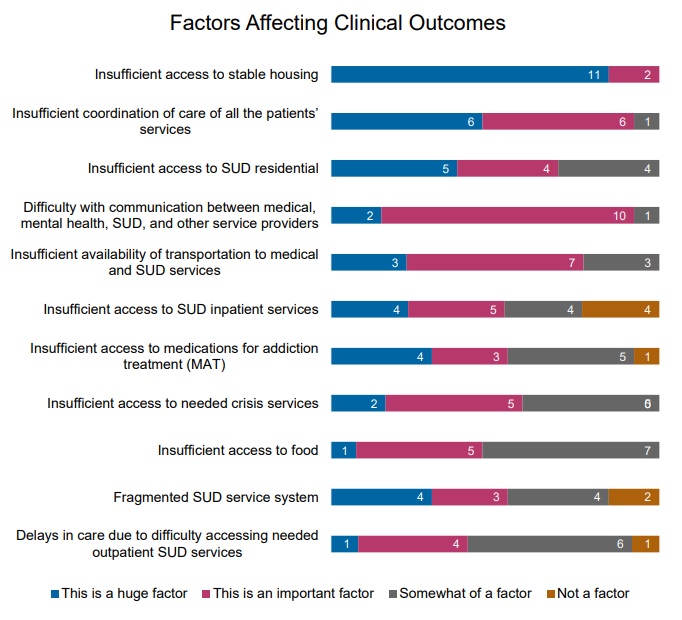

Respondents also identified factors that could negatively affect clinical outcomes for people with SUD. Insufficient access to stable housing ranked first, followed by inadequate care coordination, and limited access to residential SUD treatment. Respondents ranked 11 factors as follows:

Figure 1: Factors Leading to Reduced Outcomes, Ranked from a List of 11

Service gaps pose another significant barrier to people accessing SUD treatment, and some populations are more likely to encounter challenges than others. According to the respondents, by various population groups, Latine/Hispanic populations, African American/Black populations, and Native American/Alaska Native populations are most likely to experience SUD service gaps. By age, people who are 19−25 years old (transition-age youth) and adults ages 26−65 are most likely to face service gaps.

Opportunities to Support Improvements in SUD Care

Findings and recommendations to enhance support for individuals are informed by surveys and interviews conducted with SUD stakeholders from across the state. Recommendations highlighted in the report include:

- Investments in the workforce. By addressing the shortage of licensed clinicians and implementing peer support workers into the care continuum, the state would increase access to care. Many stakeholders have positioned themselves to meet SUD needs, but they cannot do so without an adequate workforce. Furthermore, the workforce would benefit from strengthening culturally responsive training in evidence-based practices.

- Expansion of residential treatment services and housing options. There is a growing need, especially among transition-age youth, for residential treatment and SUD recovery housing.

- Increased access to and training around harm reduction. Although stigma around harm reduction has decreased, training and access remains a barrier. Respondents highlighted the need to better manage contingencies, make methadone more accessible, establish safe consumption sites, expand medication assisted treatment for SUD and AUD, and improve the availability of Narcan.

- MH and SUD treatment integration. Offering concurrent MH and SUD treatment with the same providers can help improve access to care for people with co-occurring conditions and minimize duplication.

- Improved care coordination. Respondents suggested funding formal care coordination positions—a recommendation that is consistent with the national movement toward the coordinated care model applied in certified community behavioral health centers.

- Improved data literacy. Behavioral health organizations need support and technical assistance to learn how to track and use data to support continuous quality improvement.

What to Watch

The overarching challenges facing California’s recovery system are present in other states. These states can adapt the strategies discussed in this report to address their own SUD concerns. In California, as in other states, an important aspect of addressing SUD treatment involves strategic allocation of opioid settlement dollars. These funds, resulting from legal settlements with opioid manufacturers and distributors, are expected to play a significant role in improving the state’s SUD treatment infrastructure, especially when considered alongside available federal funding, demonstrations, and regulatory flexibilities.

Connect With Us

The upcoming HMA event, Unlocking Solutions in Medicaid, Medicare, and Marketplace, will offer more opportunities to engage with leaders from various sectors who are advancing solutions to improve access to care and reducing access disparities. Throughout the conference, federal and state officials, community leaders, and national experts will shed light on the challenges and solutions to these issues.